Business Requirements: Ensuring Your Solution is Feasible and Viable

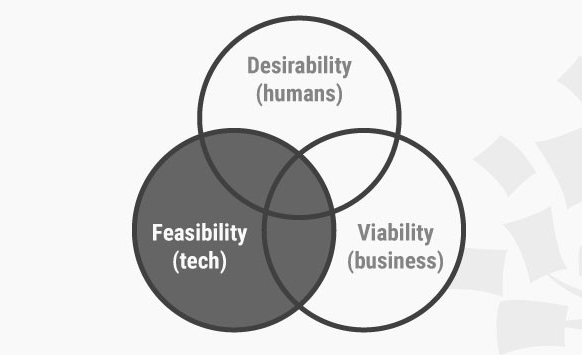

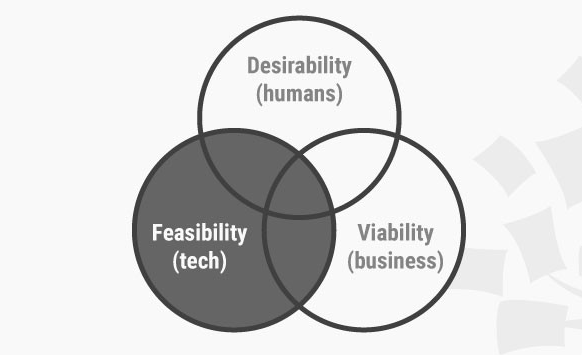

The end goal of a Design Thinking work process is to create a solution that is desirable, feasible, and viable. This means that your product or solution should not only satisfy the needs of a user but be easy to implement and have a commercial model as well. During the bulk of business requirements elicitation, function desirability would be at the forefront, as business is often at a crossroad between business needs and wants. However, it is always important to keep the focus to feasibility and viability as well as business capabilities that can be sustainable. Let us now look at the best ways you can make sure that your business requirements and solution design is feasible and viable, on top of being desirable to your users.

The feasibility of your solution is about whether or not you are able to implement your solution in an effective manner. It not only affects your company’s operations as it seeks to implement your product or service, but it also impacts your users’ experiences in a direct way. Consider, for instance, how your retail distribution network will affect where your users will have to go in order to get access to your product or service.

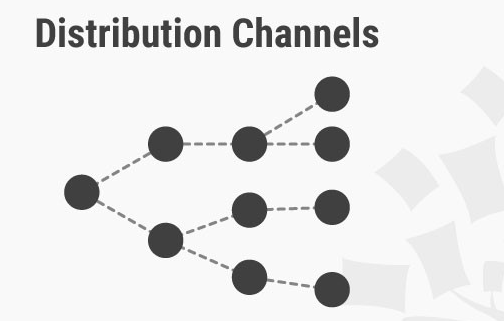

To start thinking about the feasibility of your solution, you can focus on three main areas that impact implementation: the distribution channels, the capabilities you need for pulling off the solution and the potential relationships you can form with external partners. You should think about these three factors for each of your solutions and organize an exercise to discuss them with your team-mates.

How Will Your Solution be Distributed?

To start thinking about the distribution channels of your solution, discuss with your team the possible ways your users can experience the solution. Where would they go? When and how would they experience the product or service? Why would the user want to gain access to your product? From these questions, think of as many alternative distribution and delivery possibilities as possible.

Make a list of all the potential people who — as well as channels that — will be involved in delivering the solution to your users. If you are sending your product to your users, for example, should you use the governmental postal office, engage with private courier services, or hire your own deliverymen? If your solution is for hospital patients, will a doctor or a nurse administer it? Are there other channels, conventional or unconventional, that you might use to deliver your solution?

After you and your team have come up with a list of possible delivery methods, you should then think of the pros and cons of each method. By thinking through the user experience and weighing the benefits and costs of each distribution channel, you should have a clearer picture of which ones are the most promising.

What Capabilities Do You Need for Creating and Delivering Your Solution?

Make a list of the various capabilities you will need for creating and delivering your solution to users. Include all the manpower, manufacturing, financial and technological capabilities that are necessary. For each capability, note down whether they exist in your organization. If they do, think about how you can see your solution added to your organization’s workflow and resource pool. If not, make a list of potential external sources of these capabilities in organizations and networks you can tap on. Also, consider if your organization should build up its capabilities, either to augment existing ones or to add new ones so as to create and deliver your solution.

With Whom Can You Partner Up?

If some of the capabilities you require are lacking in your organization, make a list of potential partners you can tap on to provide those capabilities. Examine if there are existing relationships between your organization or company and external companies that might be useful in this respect. Are there any government grants or programs you can tap on to partner up with service providers? Think of the various ways your company can engage with external partners — and keep in mind the various business and legal interests at stake.

From the list of potential partners, try to narrow down to a few most promising choices. You may need to involve stakeholders in your organization

to do so. Finally, think of the first steps that your design team can take in starting to reach out to these potential partners.

Ensuring the Viability of Your Solution

The commercial viability of your product or service is an important factor that affects its sustainability and long-term success. This is true even for non-profit organizations and projects because commercial viability will ensure that your solution will continue to work even without a constant inflow of funding from donors or governments.

To conduct an evaluation of your solution’s viability, you should analyze the value proposition your product or service provides, think of potential revenue sources, and consider various stakeholder incentives you can use.

What is the Customer Value You Provide?

Together with your team, think of the value that your solution provides to users. Does it provide more convenience to your customers, therefore helping them save time? Or does it provide security or safety that previously did not exist in a task? You can refer to your prototypes and notes that you have taken down in past testing sessions with users to find out what elements of your solution they find the most important or useful.

Next, try to figure out how much your users will pay for the value your solution provides. You may rely on past prototyping and empathy-gaining sessions with users, which may shed some light on how much they are willing to spend. Alternatively, you can consult experts or internal stakeholders who may have a better idea of how much your solution is worth.

What are Your Revenue Sources?

Depending on whether your solution is a product or service, or a mixture of both, it can have different sources of revenues. Together with your team, identify all the actors that will pay for the solution. How much will each actor pay for the product or service? For instance, if you are working with the government to implement a new service to people in need, will the government be paying for the full cost, or will the end users co-pay a portion of the price?

Also, think about how the payment will be made. Depending on the industry conventions, the country you are delivering your solutions to, and the needs of the users, you may want to accept cash, credit, or payment in kind for your solution. Besides the payment mode, you should also think about the most appropriate payment structure for your solution. Examples of possible payment structures include the following:

- Membership, where users pay a regular fee (monthly, yearly, etc.).

- Commission, where you earn a percentage of transaction fees enabled by your solution. (You can earn commission from the user or the user’s customer, or both.)

- Give the product but sell the refill, to encourage adoption of your solution and earn revenue once users become repeat customers.

- Subsidize the price of the solution, possibly in collaboration with the local government.

- Pay-per-use, where you charge a fee for every time a customer uses your solution.

What Incentives Does Each Stakeholder Possess?

Identify all stakeholders whom your solution will affect. Discuss with your team if the solution provides value to each stakeholder involved. On the other hand, does your solution increase the costs to some stakeholders?

Go through each stakeholder, and find out if they have any incentives or disincentives to adopt or help you with your solution. For instance, if your solution helps supermarket goers get even more value while shopping, would adopt your solution to create a disincentive for supermarkets? Consider how the proliferation of private-hire cars via companies such as Uber and Lyft has prompted strong lobbying by the taxi industries in many countries, and how it can impact the profitability of Uber and Lyft. Would your solution face similar problems from stakeholders who would be disincentivized to help you? If disincentives exist for stakeholders, try to think of ways in which you can tweak your product in order to encourage their participation.

Test It Out: Launch Live Prototypes and a Pilot

Launch Live Prototypes

After you and your team have gone through assessing the feasibility and viability of your solution, you may want to go ahead and launch a live prototype to test your solution in the market. As designers, we use live prototypes to test our solutions in real-life environments and conditions. Doing so allows you to test for the feasibility and viability of your product or service.

To begin with live prototypes, you should determine what aspect of your solution you want to test. For instance, you could focus on the distribution model of your solution… or getting users to know about your product or service. This works similarly to a normal prototype, where the first step is always to determine what needs to be tested. If you have many areas of your solution you would like to stress test or have more than one idea to test, you can consider launching multiple live prototypes at the same time; however, that would require more resources.

After you have a firm idea of what to test, you will then need to lay out the logistics behind your live prototype. Remember that you need to use live prototypes in real-life conditions. As such, you may need to rent some space, get materials to build a kiosk or apply for government approvals and licenses or permits if the need arises. If your solution is a service, you may need to create uniforms and hire service personnel.

After you have figured out your logistical plan for the live prototype, launch it. Live prototypes can last for days or weeks, depending on your needs. During the live prototype launch period, be sure to take down notes and user feedback that you have gained, and do this continually. If there are areas that went wrong, try to improve them during the live prototype testing period, and see if the improved iteration works better. Keep gathering feedback, iterating your prototype, and then testing to see if it works.

At the end of the live prototype, gather all the useful feedback you have gained from users and other people involved in the process. By now, you should have a good feeling as to whether or not your solution satisfies the three parameters of desirability, feasibility, and viability. When you feel confident in your solution (perhaps after a few runs of live prototypes), you are ready to launch a pilot of your product or service.

Conduct a Pilot of Your Solution

While live prototypes are about testing aspects of your solution in real-life conditions, pilots are about testing the entire system of your solution. It is a small step away from fully launching your solution into the market, and it should give you a very firm idea of whether the solution would work in the long term. When you launch a pilot, you are testing if each component involved in creating and delivering the system works well with other components and if the entire scale of operations can run smoothly.

The first step in launching your pilot is to make sure you have a well-thought-out logistical plan for your product or service. Consider all the parties involved — manufacturers, distributors, retailers, etc. — as well as pertinent aspects, such as legal considerations. If your solution is involved with food products, for instance, you may need to apply for a food permit.

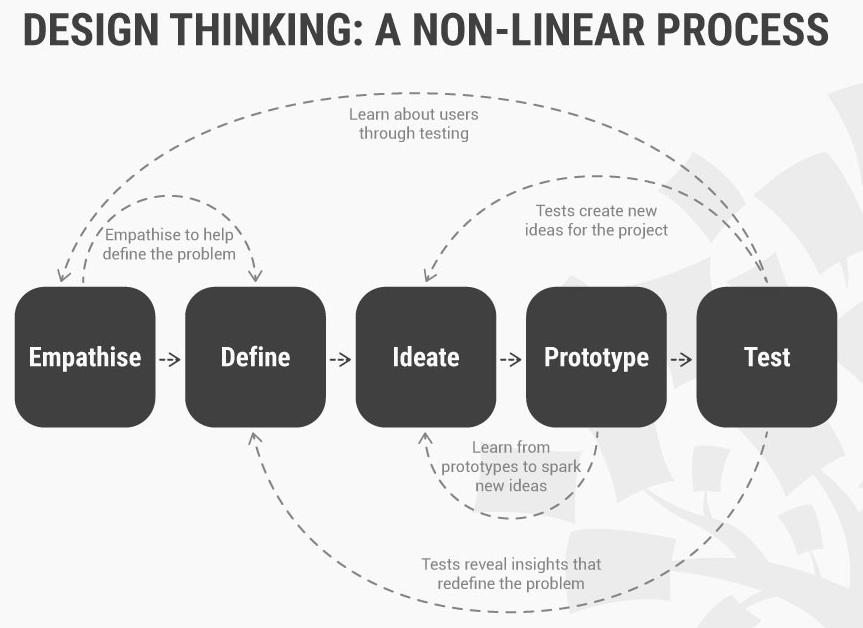

Next, consider your marketing plan. While Design Thinking might not sound compatible with marketing, the success of your solution is going to rely heavily on sound marketing. Brainstorm and strategize on how to market the values of your product or service to potential customers. Compare your solution against the existing offerings in the market, and list down the key competitive advantages you have. You can use insights about your users’ motivations and emotions you uncovered during the Empathise stage of your project to help you identify the best ways to target and engage your potential customers. At this point, it is also useful to think about the various metrics that you should be keeping track of during the pilot program.

When you have nailed your logistical and marketing plan, you can launch your pilot. Collect feedback from users and other parties involved to figure out what is working and what isn’t. You can make changes to your product or service during the pilot phase, but, ideally, the number of tweaks should be kept at a minimum, because the point of a pilot is to let you know which parts of the system are working… and which aren’t. Having too many changes might make it difficult to tell whether the system is working; indeed, any scientist will tell you that changing more than one variable in an experiment will cause confusion. Your pilot can last for months as you test both your solution and how it reacts with real-life market forces.

If your pilot is a success — congratulations! Your solution is ready for shipment to the market!

Formulate a Learning Plan to Combine Analysis and Synthesis

Throughout the business requirement elicitation process, learning plays a central role in enabling you to define business capabilities that target the needs of your users. As you begin to implement your solutions after a successful pilot run, you should continue to keep learning a key part of your organization.

After your product or service launches, you and your team should continue collecting stories from users and gathering their feedback about your solution. You can compare the stories you have collected at the early stages of your project with those collected after the project has launched. Doing so will show you the changes that your solution has made on people’s lives. The feedback you gather will also help you constantly improve the product or service to meet the needs of your users.

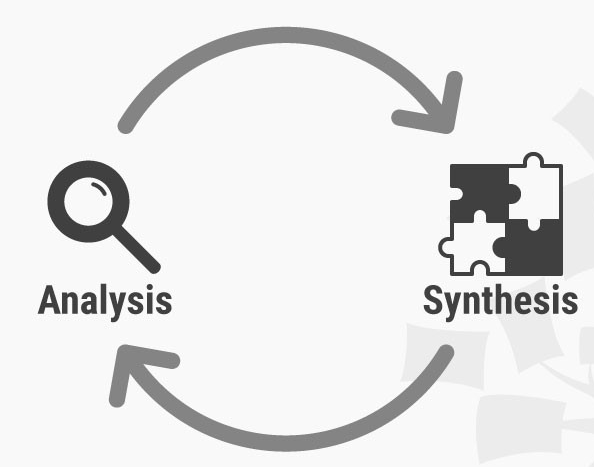

This all ties back to the constant switch between analysis and synthesis that we as solution providers have to perform. In analysis, you collect data and break down the different parts of business requirements in order to gain a fine-grain picture of the problems you are trying to solve. By actively collecting stories and feedback after your solution has launched, you are performing an analysis of your solution’s performance. Using this information, you can then synthesize and come up with ways to iterate your product or service.

To augment your learning plan and help with your analysis and synthesis, you can also track indicators relevant to your solution as well as the outcomes of your product or service. Tracking the key performance indicators will allow you to have a measure of whether your solution is performing up to expectations. You can track indicators such as the awareness of your solution or the level of engagement with users.

Before you track the outcomes of your product or service, you first have to identify the relevant stakeholders involved. Together with your team, try to define what success would look like for the different stakeholders. With this in mind, develop a plan to monitor the outcomes for each stakeholder, and use this information to feed into the next iteration of your product.

The Take-Away

In most of your software development project, you will be primarily concerned with the desirability of your solution — whether or not it meets the needs of your users. However, towards the end stages, you will need to focus on feasibility and viability as well. Think about your solution’s feasibility by considering the distribution channels, capabilities you require, and your potential partners. Evaluate your viability by thinking about the kind of value you provide to your users, your potential revenue sources, and the incentives for your stakeholders. Finally, conduct live prototypes to test your solution in real-world conditions, and then launch a pilot to test the entire system behind your solution.

At Openfactor, we pride ourselves as a technology company that places emphasis on delivering business value. And it starts by assessing and qualifying the business requirements, design, execute and deliver a fit for purpose value for money solution that gradually scales up and gradually increase with new capabilities.